Constitution and Amendments

The Constitution and the Proclamation of the Lebanese Republic

On Sunday May 23rd 1926 at 4 pm, Henry de Jouvenel set off for the Petit Sérail where he proclaimed the Constitution of Lebanon to be in effect as of that day. The actual enactment would not come into effect until 1930.

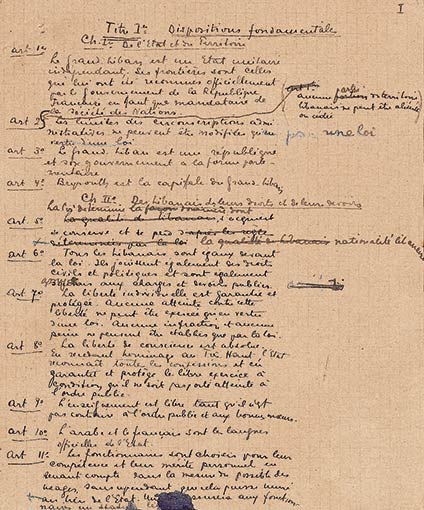

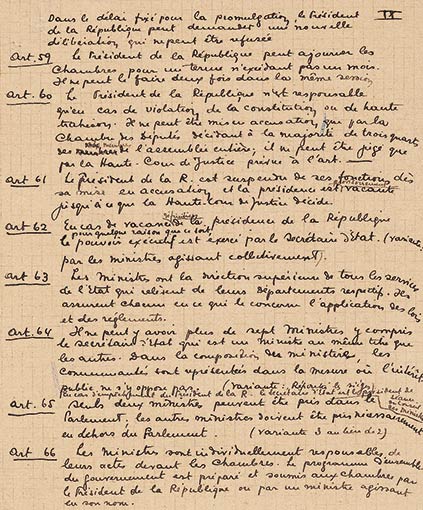

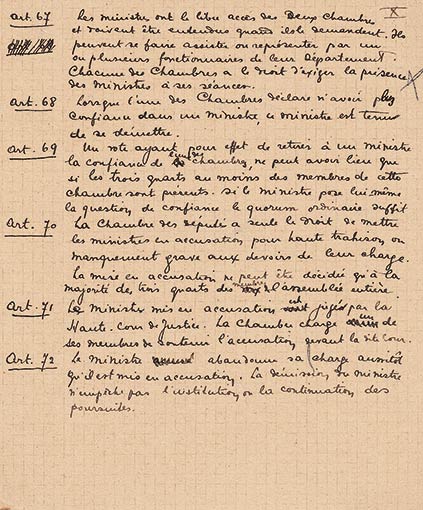

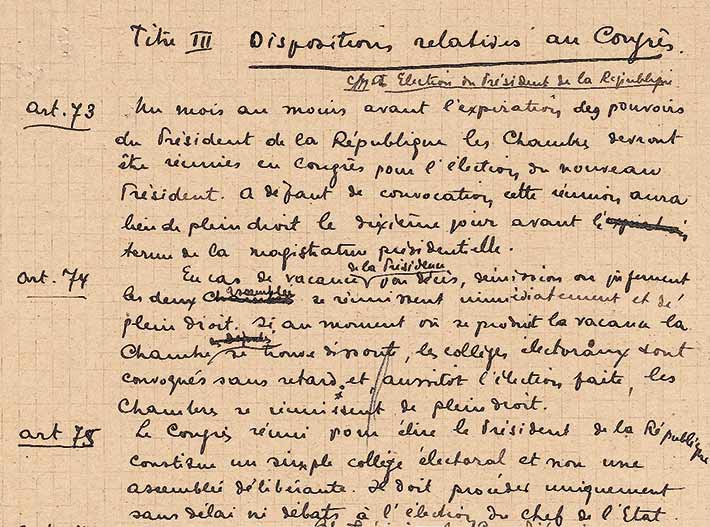

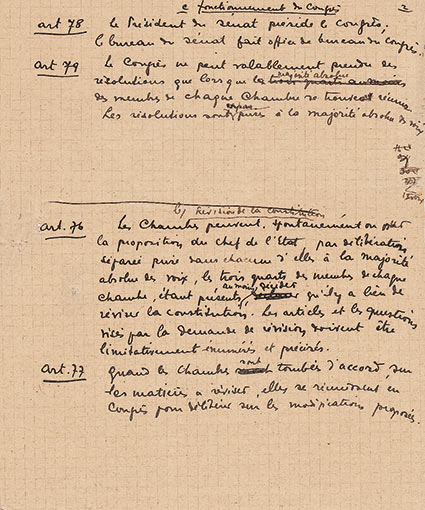

In its original form the Constitution contained 102 articles listed under six headings and subdivided into chapters. This first charter was, to all intents and purposes, a straightforward copy of the 1875 French Constitution according to which France’s public institutions were still being administered.

The final version, which was publicly proclaimed and which kept most of its statutory provisions, was quite different in principle from the first. These differences included:

-

The Presidential prerogative to appoint or dismiss ministers, the power to dissolve Parliament, the prerogative to demand a second reading of a bill and the power to enact any legislation should Parliament fail to do so.

-

Constitutional amendments procedure.

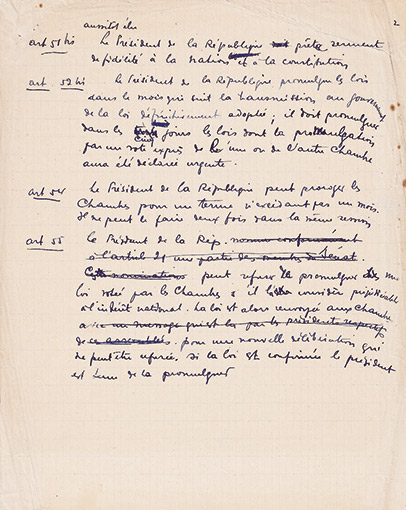

These modifications were initiated by Michel Chiha. It was his belief that Lebanon needed a firm and stable government and this would require a strong Executive which, in Lebanon’s case, was embodied by the President of the Republic. Hence the wider remit of presidential powers. As a counterbalance in order to avoid the temptation of personal power, the Constitution contained the stipulation that once the end of a president’s mandate or term of office was reached, it could not be renewed. Further various legislative procedures and quorums were also endowed with rigorous constraints for the same reason. The ultimate aim was to protect the constitution from predatory circumstances.

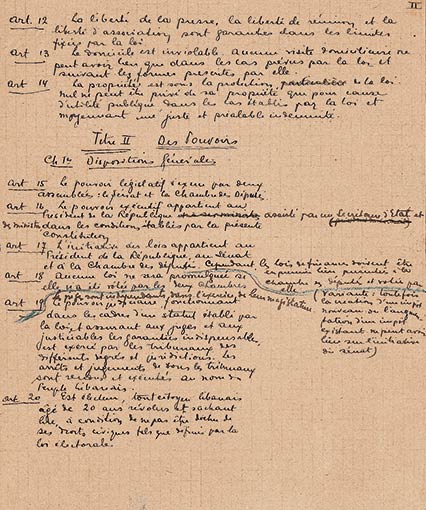

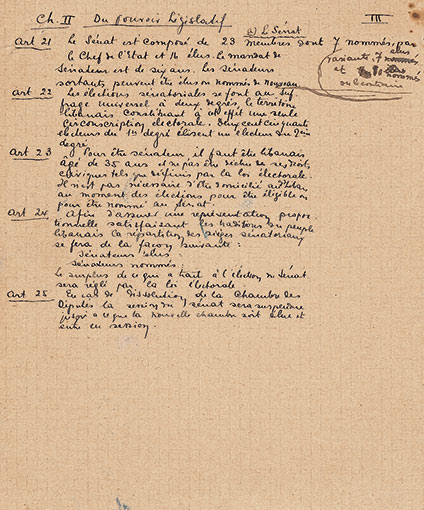

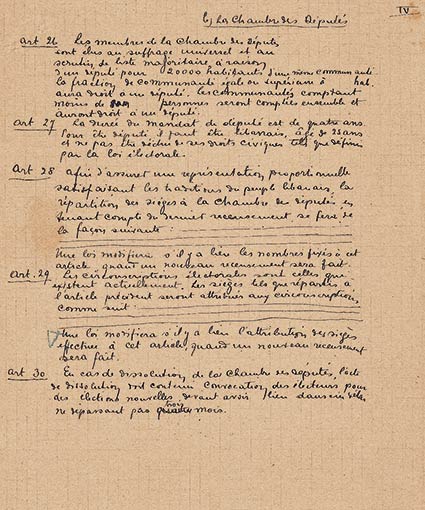

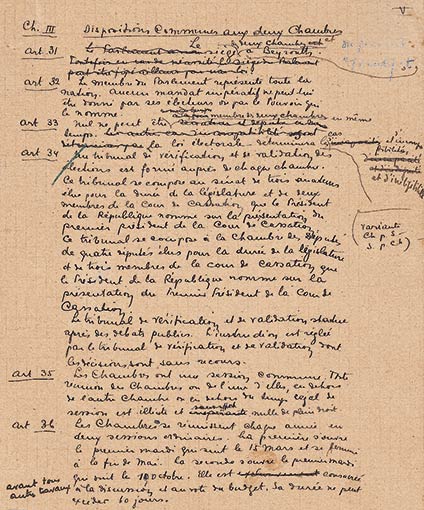

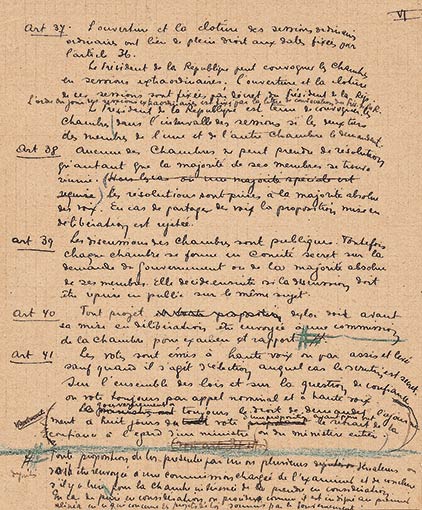

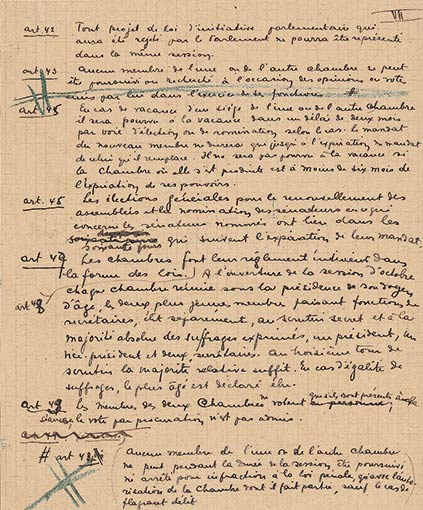

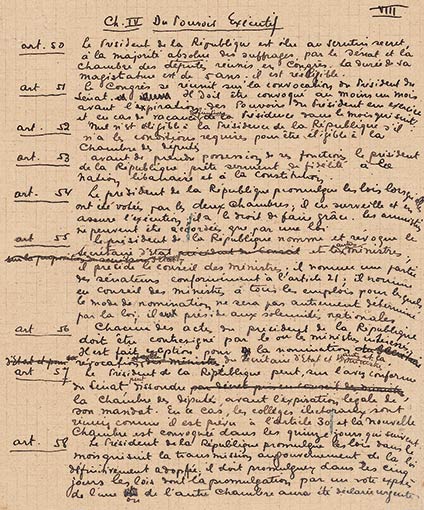

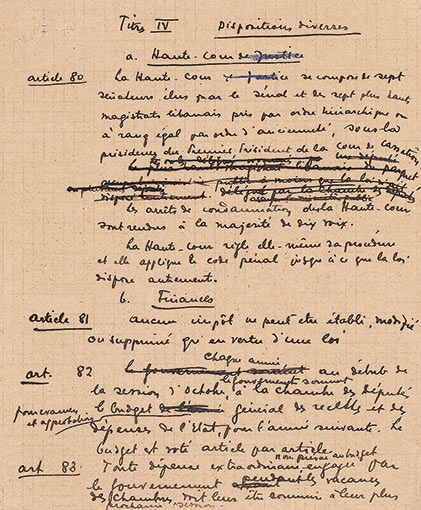

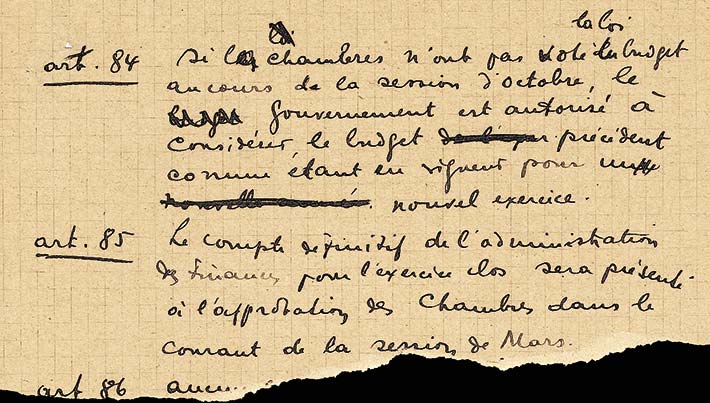

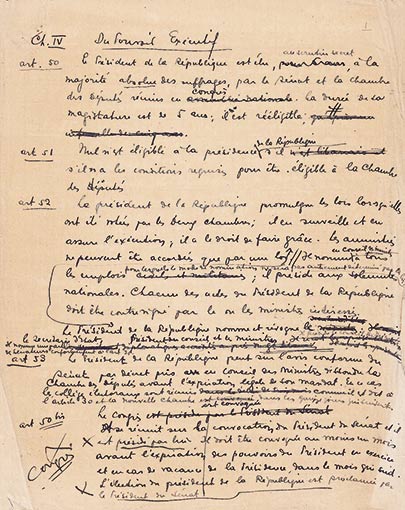

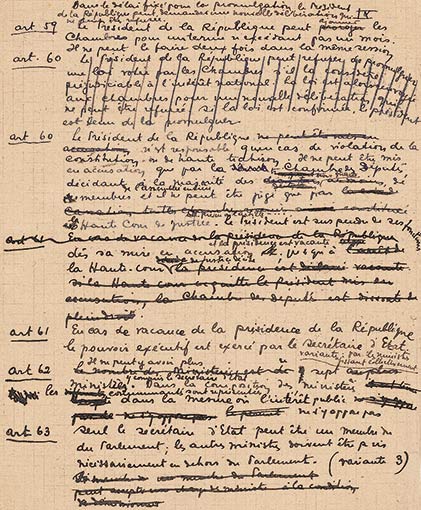

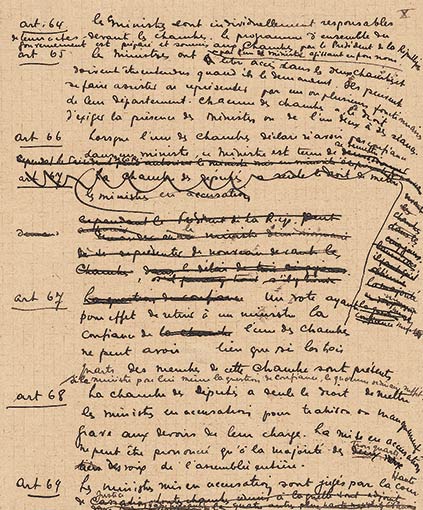

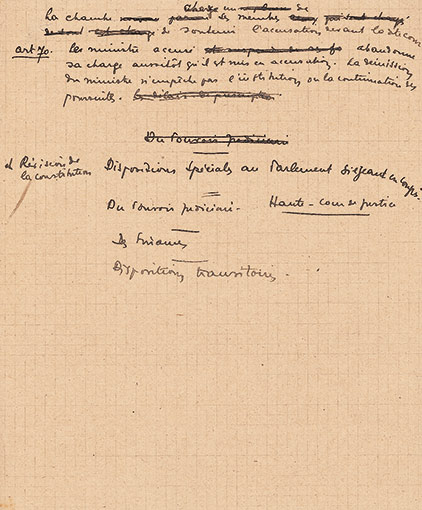

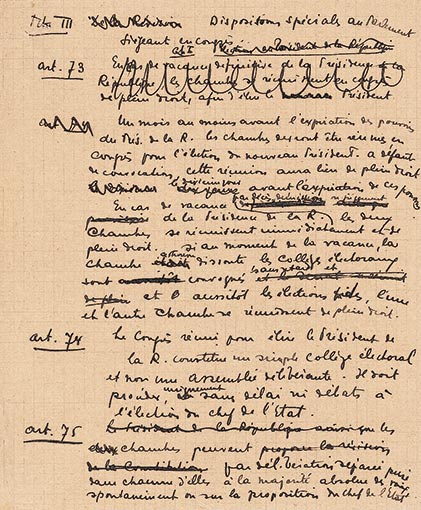

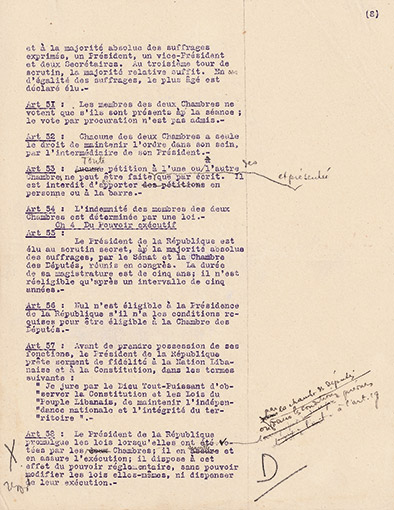

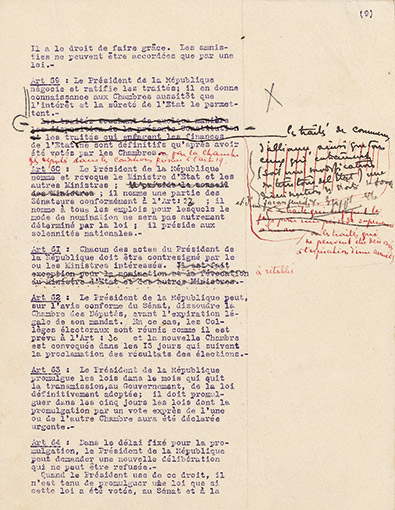

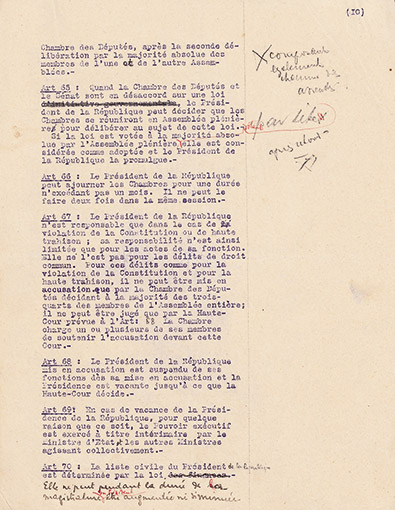

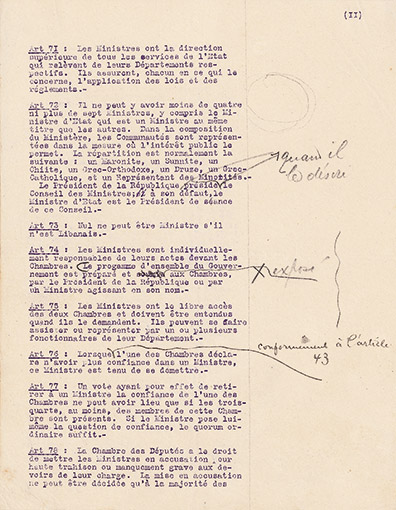

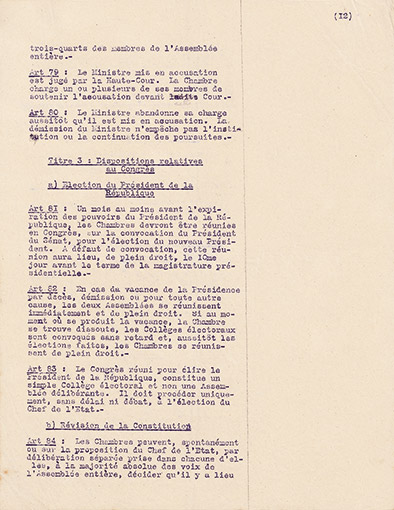

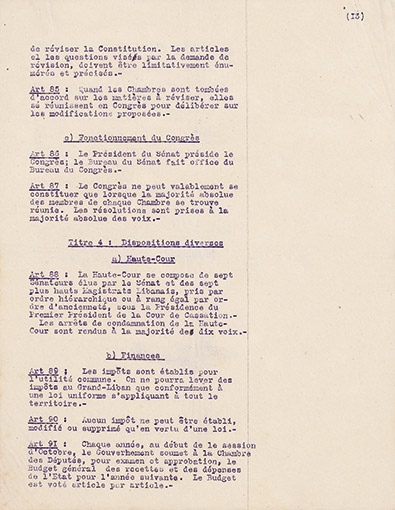

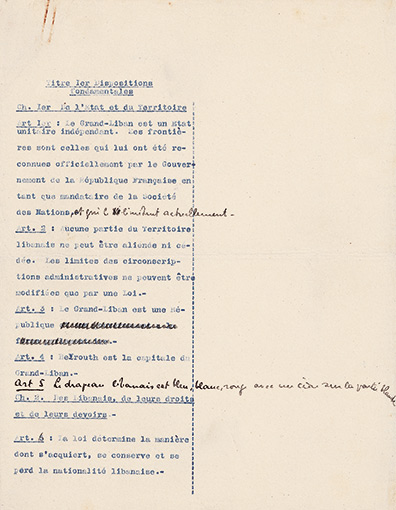

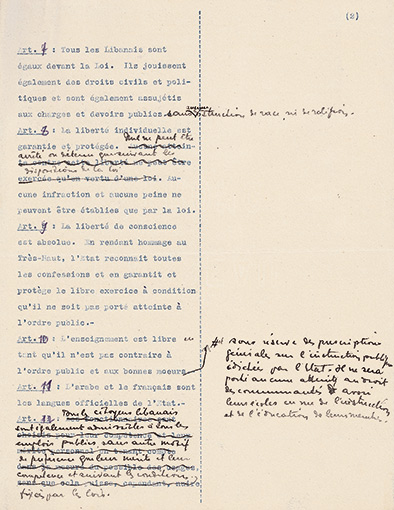

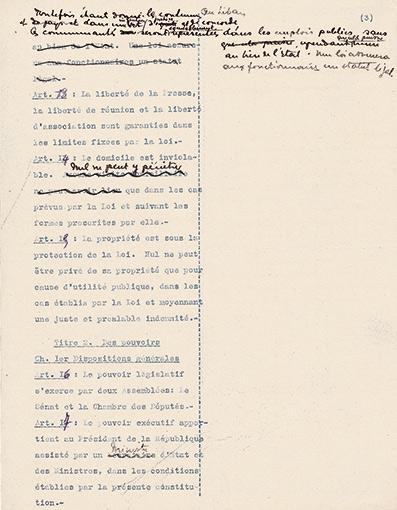

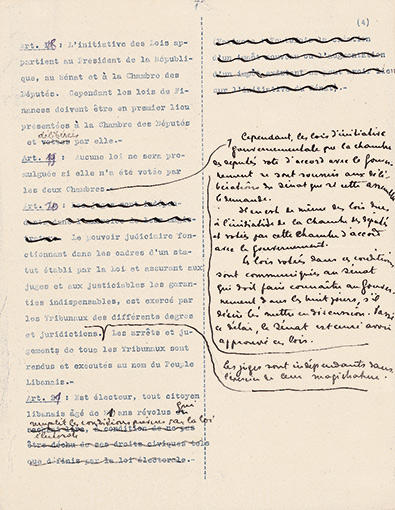

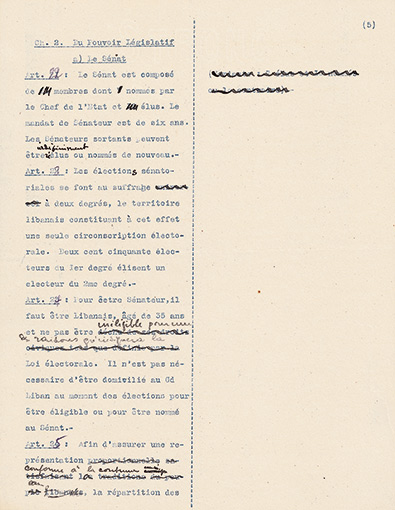

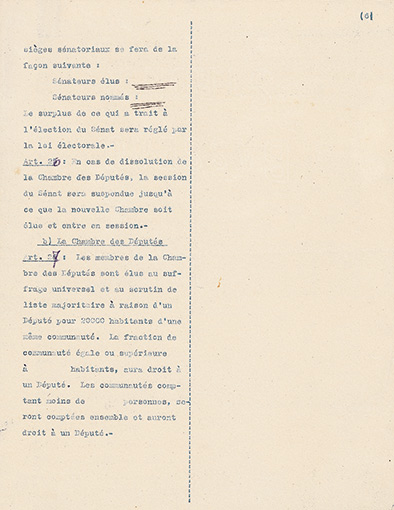

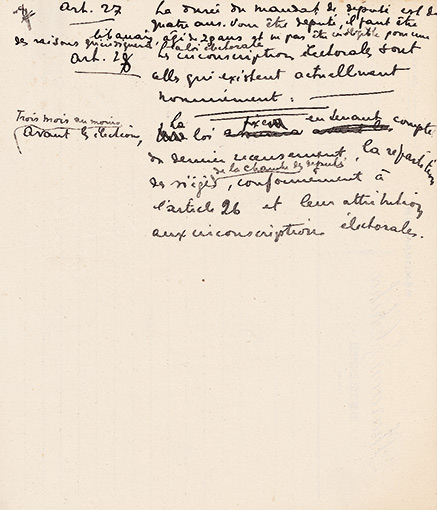

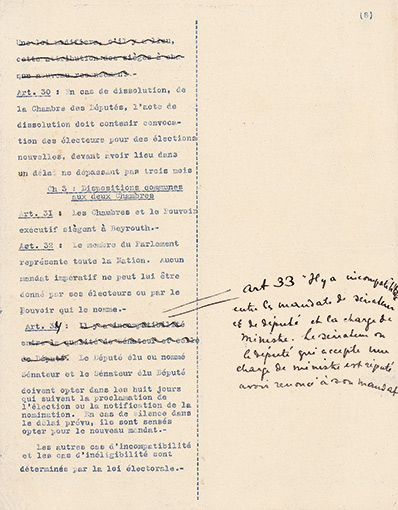

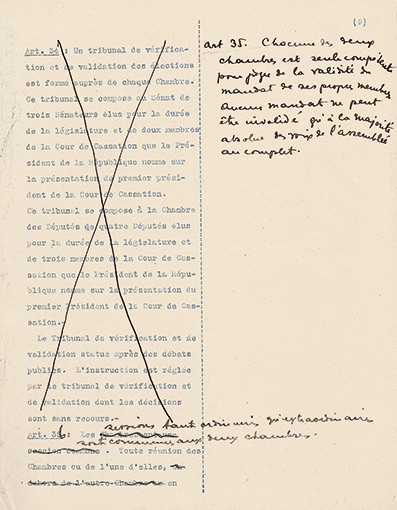

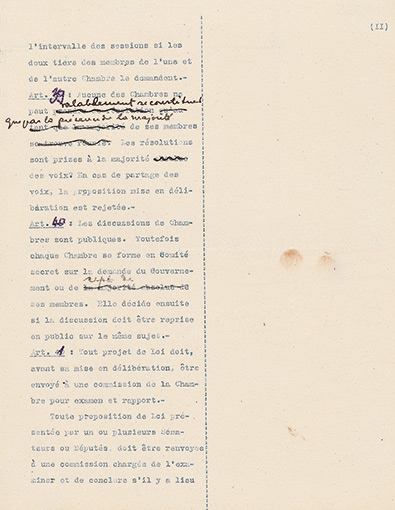

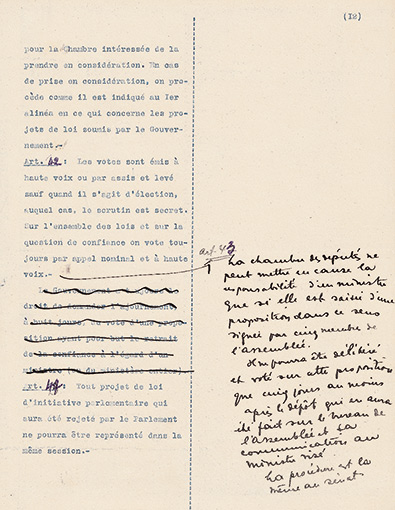

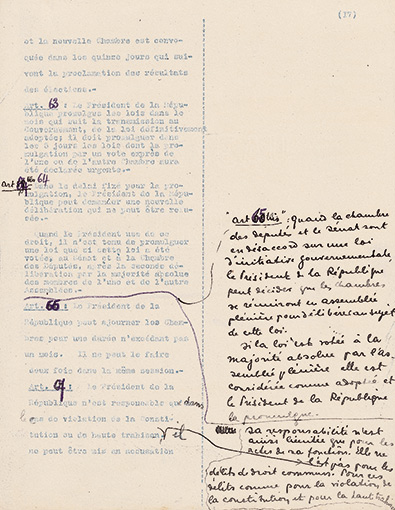

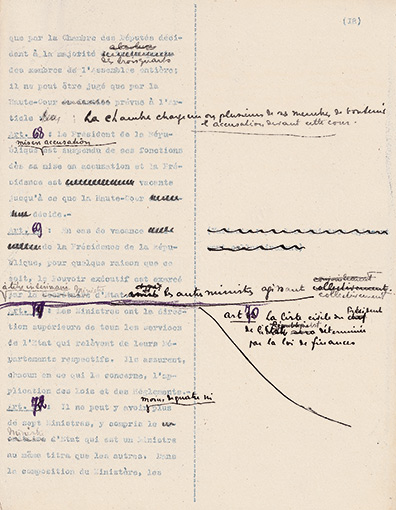

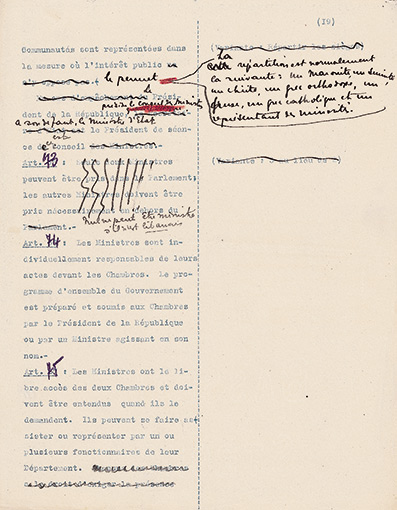

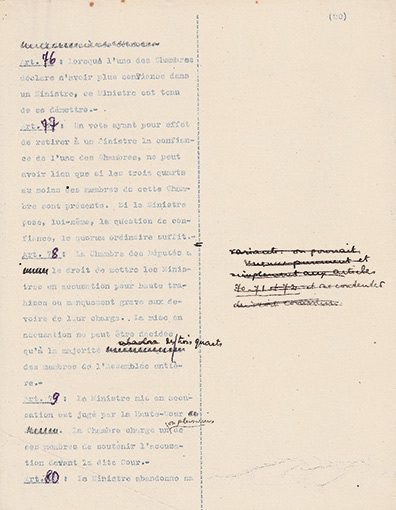

Michel Chiha played a major role in the elaboration of the Lebanese Constitution. The extent of his involvement is reflected in the handwritten manuscript and the three separate typed versions which he annotated by hand.

General structure of the Constitution

As when it was first drawn up, the Constitution includes a preamble and one hundred and two articles divided into six ‘titles’ subdivided into chapters laying out the fundamental laws governing the political entity of the State.

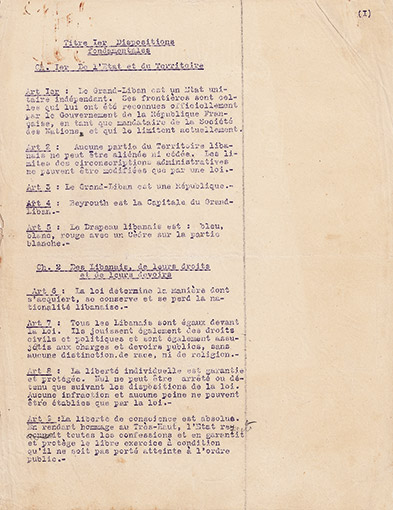

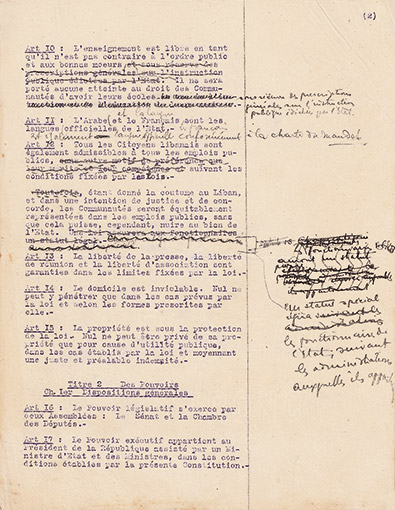

Title 1. This includes Articles 1 to 5 outlining the basic conventions stating the fundamental principles of the State and its territory. Articles 6 to 15 cover the citizens of Lebanon, their rights and their national obligations.

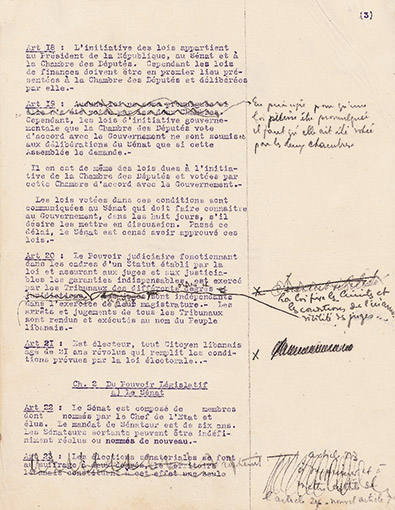

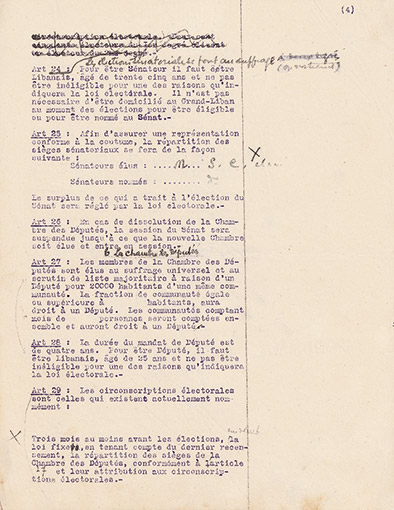

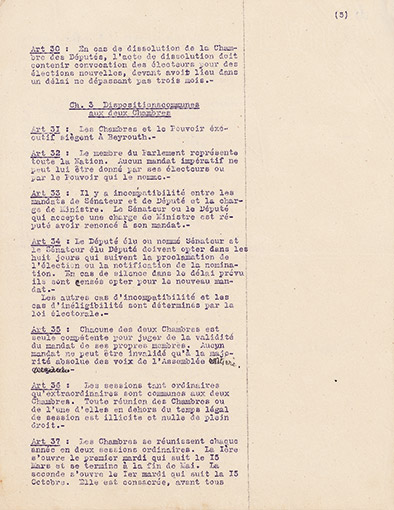

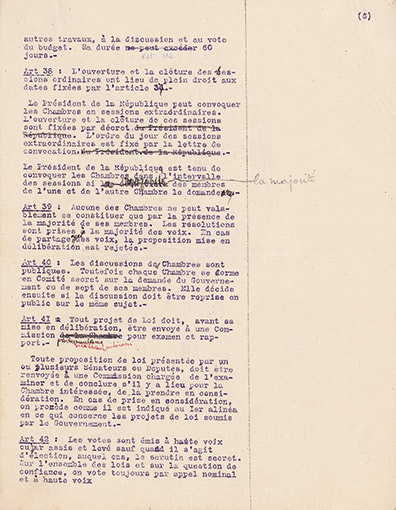

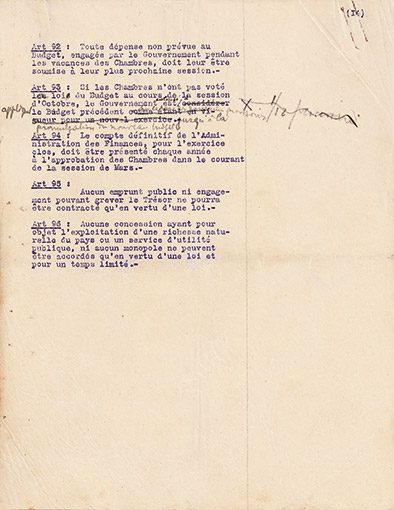

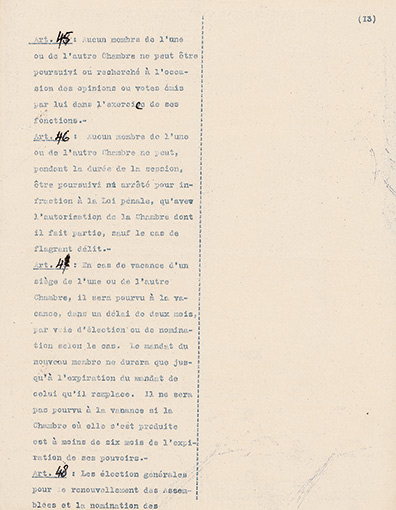

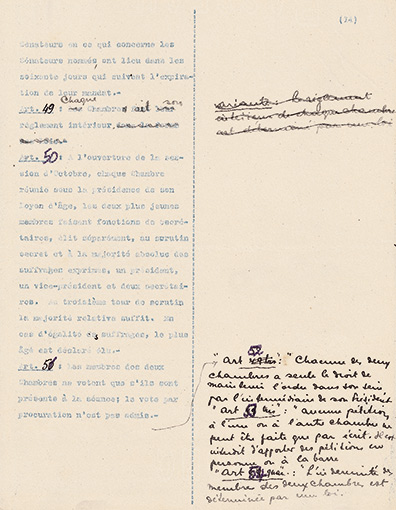

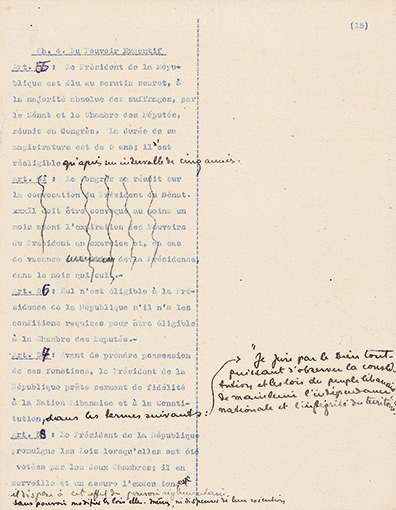

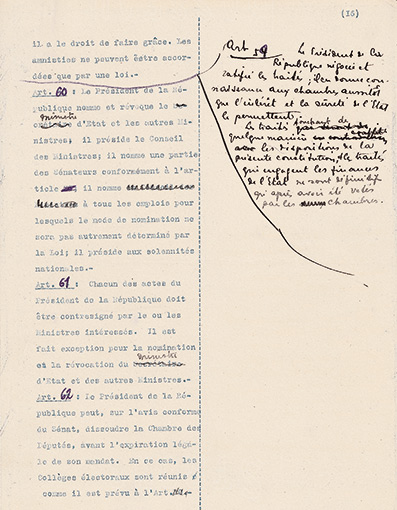

Title 2. This covers the rules of government, the very essence of the Constitution, spread throughout four successive chapters. First part (Articles 16 to 21), includes the universal measures defining the three branches of government and their relevant components. Second part covers the tenets of legislative power, in force during the bicameral stage of Parliament (Articles 22 to 25) and of which only two measures remain (Articles 24 and 25). It also covers the formation of the Chamber of Deputies, the only remaining legislating body. Third part(Articles 26 to 48), covers provisions related to the Chamber. Fourth part (Articles 49 to 72), covers the powers of the Executive.

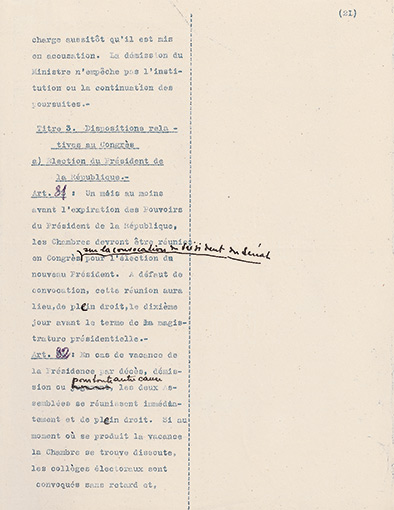

Title 3. Consists of three paragraphs:

Paragraph A (Articles 73, 74 and 75), details the procedures for the election of the President of the Republic.

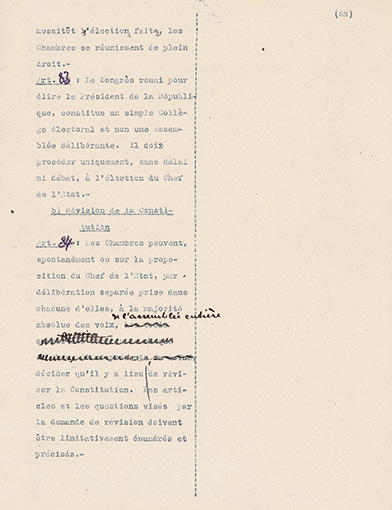

Paragraph B (Articles 76 and 77), details the procedures relating to amendments of the Constitution.

Paragraph C (Articles 78 and 79), describes the role of the Assembly once the aforementioned procedures have been implemented.

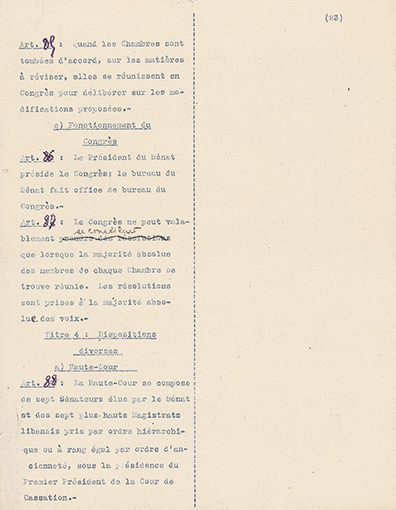

Title 4. Contains two paragraphs:

Paragraph A (Articles 80), outlines the composition of the High Court.

Paragraph B (Articles 81 to 89), outlines the rules guiding the management of Public Finance.

Title 5. Includes Articles 90 to 94 pertaining to the formalisation of French mandatory rule over Lebanon and the League of Nations which were first revised by constitutional amendment on November 9th 1943 and again on January 21st 1947. Also includes provisions relating to the Mandate Authorities and the League of Nations.

Title 6. Includes Articles 95 to 102 which involve the settling of any remaining or provisional issues. It no longer exists in its original form having undergone radical modification under the constitutional amendments of 1943 and 1947. These affected in particular Article 95 which had endeavoured to guarantee in public service jobs and government ministries an equitable balance of employees drawn from the various sectarian communities, and Article 101 which repealed all legislative measures contradicting the constitutional amendment of 1943.

Of the one hundred and two articles of the original text, and including the 1927 abrogations (Articles 22, 23, 96 and 100 all relating to the Senate), the 1929 abrogations (Article 69 which established the size of a quorum required for a vote of no confidence), the 1943 and 1949 abrogations (Articles 90 to 94 pertaining to mandatory authority and the League of Nations) all of which come to a total of 13 amended articles, the current Constitution now consists of only 89 current articles.

Quotes from E. Rabbath’s “La constitution libanaise”, 1982, Beirut.

Article 90: The authority established by the present Constitution is subject to the prerogatives and responsibilities of the mandatory power as specified in Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations and the Mandate Charter.

Article 91: The state of Greater Lebanon intends to apply for membership of the League of Nations subject to a favorable recommendation by the mandatory authority.

Article 92: The present Constitution proclaims itself to be that of a peaceful nation which intends to maintain harmonious relations with all nations, particularly with neighbouring countries under a French Mandate with which it intends to foster reciprocal conciliatory and peaceful alliances.

Article 93: The present Constitution of Greater Lebanon includes a solemn commitment to refer for arbitration by the mandatory authority all conflicts that could potentially endanger the state of peace. In this matter, Greater Lebanon agrees to enact any necessary measures in conjunction with its neighbours or any other affected nation to ensure that all conflicts are referred summarily for arbitrage.

Article 94: The Lebanese Government will agree with the mandatory authority the formation of a diplomatic delegation to be sent to Paris and will appoint a diplomatic attaché to the French diplomatic and consular missions in cities abroad where there are enough Lebanese residents to justify said appointment.

The Lebanese Government will do everything in its power to maintain close contacts between emigrant Lebanese and the mother country.

Article 95: As a temporary measure, in conformation with the stipulations of Article 1 of the Act of Mandate and in the interests of justice and harmony, Lebanon’s sectarian groups will be equally represented in public service jobs and government ministries on condition that this does not interfere with the interests of the State.

Article 96: The allocation of seats in the Senate will be shared between the sectarian communities in accordance with Articles 22 and 99, and in the following proportions:

5 Maronite, 3 Sunni, 3 Shia, 2 Greek-Orthodox, 1 Greek-Catholic, 1 Druze and 1 Minority.

Article 97: Once the present Constitution has been ratified, the current Representative Council will be known forthwith as the Chamber of Deputies and will remain in session until the end of its mandate.

Article 98: In order to fully implement the present Constitution as soon as possible and as stipulated in Articles 22 and 96, this first Senate will be appointed by the High Commissioner of the French Republic for a period no longer than the end of the year 1928.

Article 99: After its appointment by the French High Commissioner, the newly constituted Senate will convene for its first session in order to nominate a candidate for the President of the Republic, for the vice-President of the Republic and for two Secretaries of State as stipulated in Articles 44 of the present Constitution. This procedure will take place after the election of a new Assembly.

After the election of a new Chamber of Deputies, the assembly must appoint its own procedural officers during its first session as stipulated in the aforementioned Article 44.

The duly appointed procedural officers of both Chambers will remain in office until the following October.

Article 100: Within one month of forming the Senate, its President will convene the members of congress in order to elect a President of the Republic.

Article 101: As of September 1st 1926, the State of Greater Lebanon will be known as the Lebanese Republic with no further changes or modifications of any sort.

Article 102: The present Constitution is to be placed under the protection of the French Republic as the mandatory authority appointed by the League of Nations. All legislative measures in contradiction with the present Constitution are abrogated.

The Need for a Powerful Executive

“… What we want more than anything is government stability but not one based on incompetence or self-indulgence…”

“…the equalising factor lies with the Head of State who, in accordance with the terms of the Constitution, can appoint or dismiss ministers without the need for further endorsement. In this respect, our Constitution is rather unique. Mirroring the framework of a European parliamentary system, it nevertheless gives the Head of State the same sort of prerogative as in the American executive system. In my opinion, we don’t see this nearly enough…”

“…In Lebanon, the Head of State can dismiss a government on his own authority; he can form a new government at will and can dissolve the Chamber without further formalities. This immense power, if used wisely and boldly, would put an end to excess and would bring the Republic to heel if necessary which is what counts when trying to achieve a balance between stability and prerogative, to fulfil the will of the people against that of a Chamber replete only with self-interest…”

“…the stability of our government, so admired abroad, is based on the facility of renewing its authority from within…”

On government stability, M. C., Le Jour, July, 5th , 1950.

“… the 1926 Constitution, in which I was personally involved and which I mostly drew-up, was meant to have two Chambers. The first appointed Senate lasted a year because it blocked all attempts to legislate and its demise resulted in a Chamber composed of the most peculiar mixture of elected and appointed deputies. Members of the defunct first Senate were simply appended to the Chamber of Deputies. Those implausible days are over and under no circumstances should we resurrect the unfortunate circumstances which ‘trapped’ the system in a morass of chronic turmoil for 25 years. It is my belief that the Chamber of Deputies should be reformed. The Executive retains the power to dissolve it and the mere threat of doing so would impel the Chamber to pull itself together. Instead we are led to believe that it is preferable to reinstate a Second Chamber precisely in order to curb the Executive from abusing its powers. How ironical! There are surely enough experienced politicians [not to mention experts in Constitutional Law] who can clearly see where this would lead…”

“…However, before any proposed constitutional reforms are put forward, be they based on previous experience or on practical requirements, I must reiterate the need in this country for moral reform. Could this possibly be the real purpose of a Second Chamber? If so, why not spare the nation the trouble and deal with the task of moral reform ourselves?

Something we ought to think about, M.C., Le Jour, June 13th, 1948.

“…Since the Revolution, France has infected a large section of Europe and the world with its fever for constitutionalism. The French find it natural to change or amend a constitution. Lebanon has also been affected by the constitutional bug. No sooner had we drawn up the 1926 Constitution than we revised it in 1927 and again in 1929, largely due to French pressure. It was often criticised and suspended, again due to the prodding of an anxious and changeable France. Nevertheless, if it has managed to survive in spite of misfortune, this is because it is robust! Its critics often make the mistake of not reading the detail of it, something which has not gone unnoticed, but that’s another story……”

Starting with the “Directoire”, M.C., Le Jour, January 26th, 1946.

Chiha on Appointed Deputies

“…You can appoint just about anything you want but you cannot appoint Deputies.”

Appointed Deputies, M.C., Le Jour, July 8th, 1950.

“Under the tacit agreement which covers the current elected chamber, there are now more than enough appointed deputies without adding insult to injury by increasing their numbers through legislation. On the whole, the elections alone will always ensure more than enough appointed deputies on account of political pressure and the long lists of favours owed!”

The same old story, M. C., Le Jour, May 12th, 1949.

Constitutional Amendments were enacted in 1927 and 1929 which were accredited to Henri Ponsot the French High Commissioner.

The first most significant change was the abolishment of the Senate and the integration of the former members of this Upper House into the Elected Chamber of Deputies, thereby creating a new parliamentary entity known as Appointed Deputies. These members composed up to one third of the Chamber of Deputies and their presence would not be revoked until March 1943.

The second change involved the conversion of individual ministerial responsibility into collective Cabinet responsibility.

The third change involved the redrafting of Article 58 giving the President of the Republic the authority to enforce any bill of law upon obtaining a Council of Minister Executive order subject to the condition that said bill was deemed urgent, and more relevantly, had not already been voted on by the Chamber within forty days of it first being tabled.

“…Lebanon is free to modify its constitution as it sees fit: this is a prerogative engendered in the Constitution itself [Article 76 and so forth]…. God knows the 1927 Amendment made it difficult enough to exercise that right. Under the eagle eye of the distinguished George Catroux it wrapped the Constitution in a cocoon of stringent precautionary measures making it difficult to amend in the future…”

“…the notion of appointing deputies would be like electing army officers. The contradiction between the ends and the means is glaringly obvious. The reason why Lebanon has had ‘appointed’ deputies for the last fifteen years is because in 1927 members of the State Council or Senate were incorporated into the Chamber of Deputies in order to end their overcautious systematic blocking of all legislation. When it wasn’t the Chamber of Deputies, it was the elder statesmen who were holding the legislative procedure in check, making it impossible to conduct government affairs. The appointed deputies had all been members of the 1926 Senate, chosen by Henry de Jouvenel, himself a French Senator and High Commissioner of Lebanon. This nominated Senate, part of the 1926 constitution, was based on the expectation that it would lend itself to calming and safeguarding the political process. However, Lebanon in 1949 is not the same as it was 25 years ago. Conventions became enshrined and the State, particularly the nature of its independence, has changed. The 1927 Chamber of Deputies inherited the venerable senators and this unexpected paradoxical development brought about the phenomenon of appointed deputies. Thus, legally and to the detriment of all, the Government became the principal nominator in all representative elections leaving the electorate to choose from amongst those it had discarded. In fact, the appointed deputies would already have been chosen before any election was held and furthermore, would include candidates who had lost in the polls. Thus Providence and the change in the composition of the Senate engendered the institution of appointed deputies, a phenomenon which by virtue of its very nature always interfered with the effectiveness of the Chamber of Deputies. The notion of reinstating it would be preposterous; it would make us ridiculous and would openly suppress what little is left of public opinion in this supposedly free and independent nation…”

At the same time, M.C., Le Jour, November 7th-8th, 1943.

The Constitutional Amendments of 1927 and 1929

In the ensuing years the need to revise the Constitution became increasingly apparent (especially the need to abolish a staid and obstructionist Senate) and as a result Henri Ponsot, like his predecessors French High Commissioners, approached Michel Chiha to help bring this about, not only because of the latter’s legislative experience but also because he fully agreed with the need for reform (hence the Constitutional Reforms of 1927 and 1929).

In addition to his involvement with the proposed legislative amendments to the Constitution, as Head of the Parliamentary Finance Committee, Michel Chiha was also responsible for drawing up several fiscal and monetary policy recommendations aimed at establishing a coherent Government Budget.

“…Contrived by Henry de Jouvenel, the 1926 Senate lasted exactly one year. It had been entirely appointed by the High Commissioner and included sixteen of the most virtuous parliamentarians. By the end of the year, the political system was so overburdened and so hampered by this new assembly that it became necessary to do away with it. The outcome of its abolishment was the advent of ‘Appointed Deputies’, an entirely new phenomenon in the world, one arising from the unexpected inclusion of numerous senators and deputies. I can attest to these facts because I took part in them. I was a Deputy for Beirut at the time and, even though there was no real need for such excessive caution, I drew up this very Constitution with its unavoidably problematic Senate due to the obdurate persistence of Henry de Jouvenel, himself a French Senator. A superfluous persistence when in fact every precaution had already been included to make sure that the new Senate could interfere as little as possible. However, as is its wont, reality overcame theory in record time. If the current Government is toying with the idea of creating a Senate, it would do well to take on board these facts as soon as possible. In this country, it is not the Chamber of Deputies that requires a ‘Chamber of thought’ but the Government itself. On the other hand, as a joke, should it go ahead now and create a Senate of its own, the result could very well be that it ends up with far more control over both chambers.”

To inspire thought , M.C., Le Jour, June 16th, 1950.