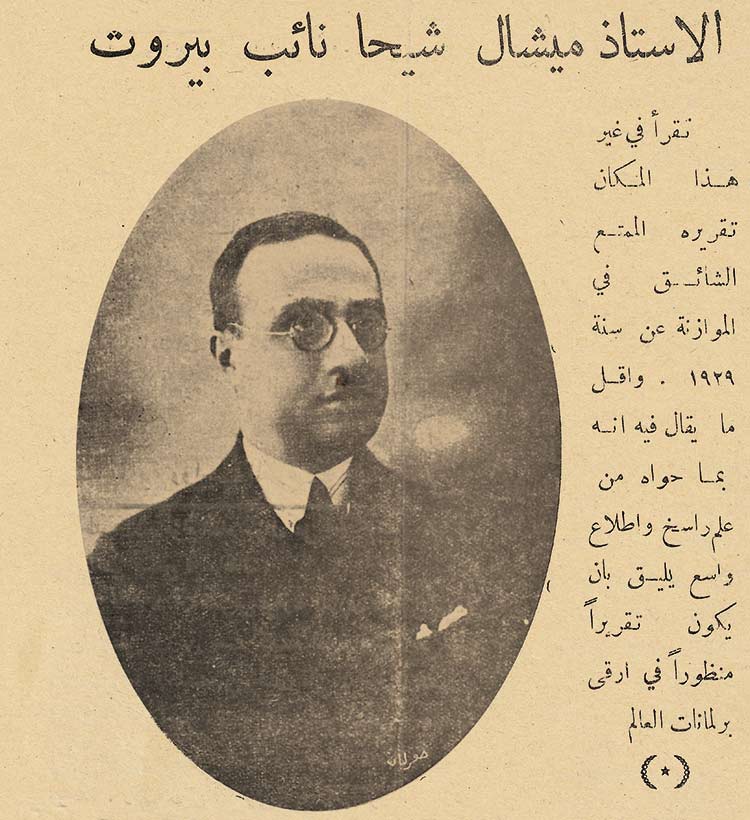

Deputy for Beirut

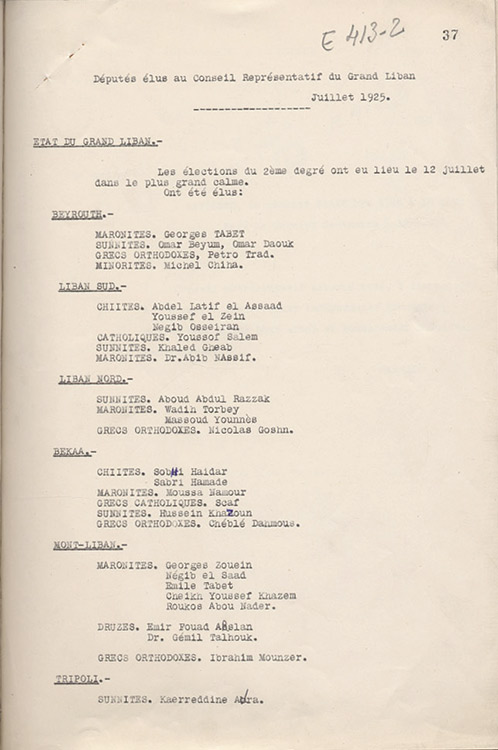

Michel Chiha formally but reluctantly entered the political arena by running in the 1925 legislative elections. He stood against Ayoub Tabet and was duly elected Deputy of Beirut for religious minorities in a parliament that was to oversee some of the most memorable events in the nation’s history including the Druze Revolt, the Damascus Uprising, and the proclamation of the country’s Constitution.

His inherent reluctance to take part in active politics was the reason why he hesitated so long to declare himself a candidate for the minority seat. Although he eventually committed himself under pressure from his friends Omar Beyhum and Omar Daouk who very much wanted him on their joint electoral list, he was so horrified by the unscrupulous stunts generally employed during an election campaign that he almost resigned his candidature right in the middle of the election.

Only a strong sense of loyalty to his fellow candidates prevented him from opting out completely. In the event, the entire joint list won their seats in spite of the personal opposition of both the then-new High Commissioner General Maurice Sarrail (2 January 1925 – 10 December 1925) and Léon Cayla, his appointed representative, whose outlook on the future of Lebanese independence clashed in terms of policy with both the previous French administration and the incumbent Lebanese representatives.

Michel Chiha’s original reluctance to enter the full-blown parliamentary arena was well-founded. He was singularly ill-suited both by nature and lifestyle to the career of a Member of the Chamber of Deputies. It entailed far too many servile obligations incompatible with a quiet and reflective lifestyle and anathema to a man averse to intrigue and shoddy compromise.

His reluctance to run in the 1925 elections was based on his knowledge that he would have to act against his natural instincts. In order to coerce him into participating, his friends resorted to intense pressure to convince him that his natural abilities were essential to the best interests of his country, especially at such a crucial time. However, no amount of pressure or coercion would convince him to repeat the experience, and therefore as soon as he had fulfilled what he deemed to be his civic duties in 1929, he gladly withdrew from elected public office and never again ran for re-election.

After he eventually committed himself to his friends Omar Beyhum and Omar Daouk, who had pressured him to put himself forward as a member of their joint electoral list, the entire joint list won their seats. In contrast to preceding French High Commissioners and administrators, Sarrail and Cayla considered Michel Chiha to be a reactionary die-hard and a puppet of the Church. Auspiciously, their administrative authority was not to last very long.

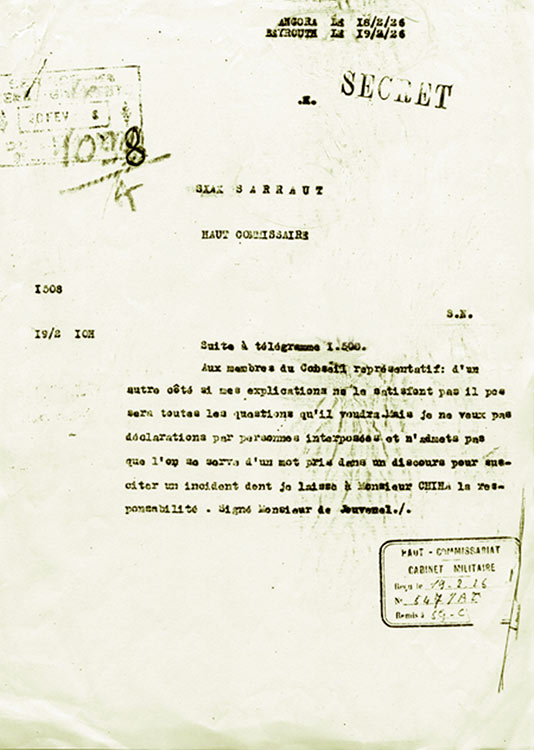

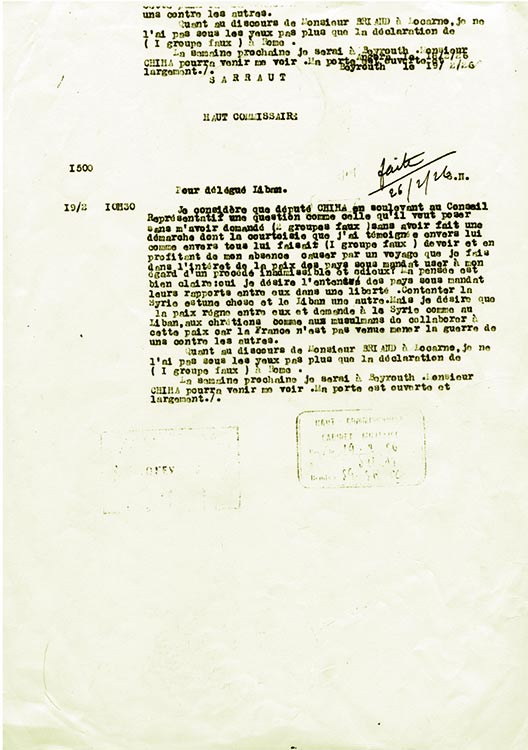

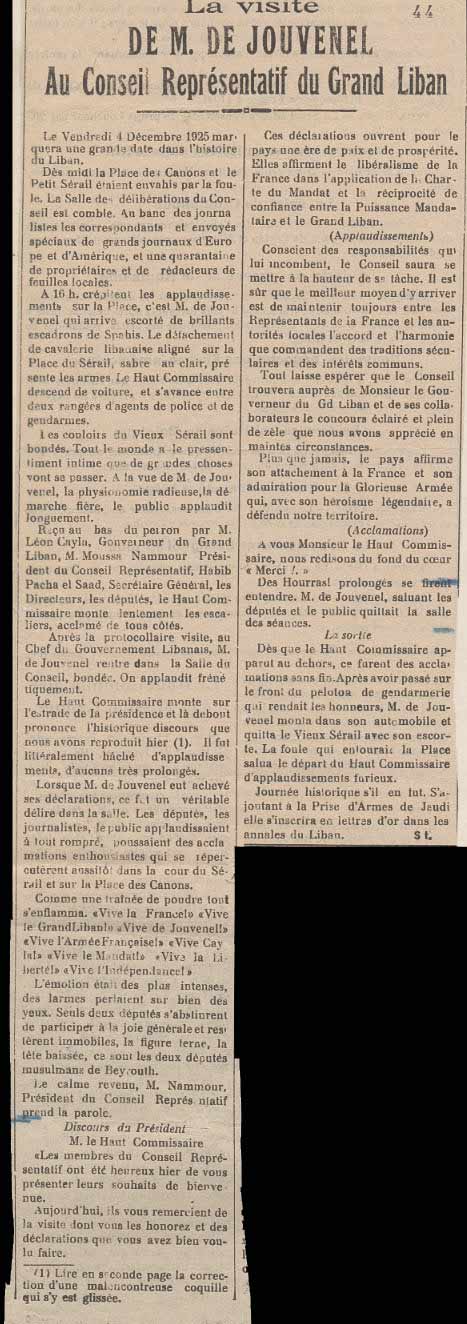

The lacuna created by the departing hostile mandatory authority was quickly filled by the arrival of Henry de Jouvenel ( December 10th, 1925 – September 3rd, 1926), who was keen to reinstate vigorous negotiations between the French authorities and the local legislative.

The new High Commissioner immediately proposed the drafting of an organic statute which would result in the Constitution of 1926. Throughout its drafting, Michel Chiha was closely involved with the new policy advisors of the French High Commission much more in tune with his own aspirations as well as those of his former ally General Maxime Weygand.

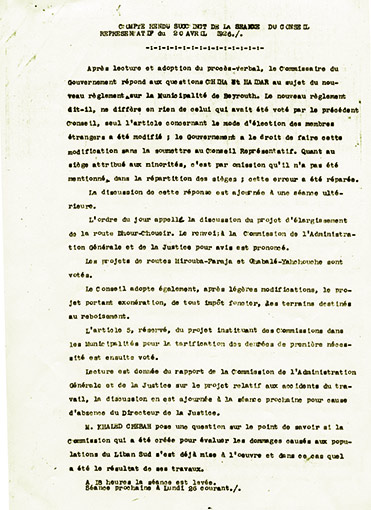

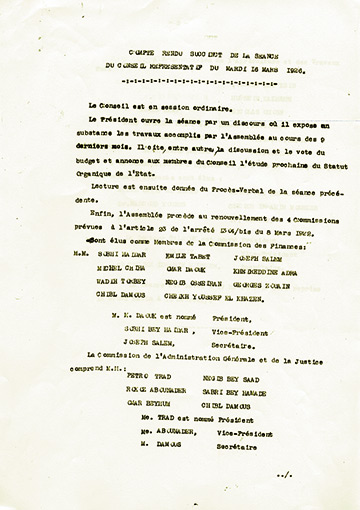

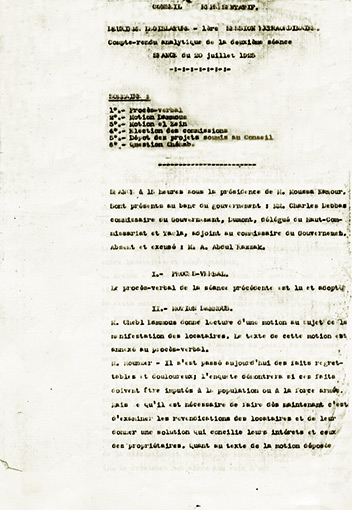

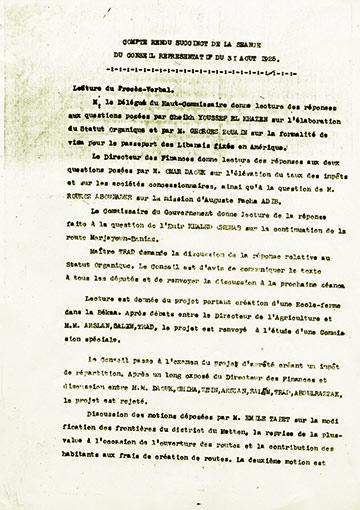

As one of the three-man commission, including Pedro Trad and Omar Daouk, appointed to prepare a preliminary draft of the Constitution, Michel Chiha acted as its spokesman, and for all intents and purposes, it was he who composed the details of the Act that was subsequently passed by the Chamber of Deputies. His frequent intercessions on almost every aspect of the proposed bill can be found on page after page of the official parliamentary bulletin.

During the second phase of Lebanon’s political emancipation, he became even more involved in drafting the details of the proposed constitution, overseeing the institution of universal suffrage by consulting and horse-trading with the various political parties, political family clans, and feudal lords.

Nonetheless, his four years in the Chamber of Deputies had endowed him with considerable constitutional and fiscal experience and he was often called upon to represent the State on special assignments. One such diplomatic mission, undertaken in 1946, had him in charge of establishing formal diplomatic relations between Lebanon and the Vatican. He later undertook fundamental assignments involving the financial infrastructure of the country.