The Monetary Agreement

Independence of the Lebanese Currency

The value of the Lebanese Pound was officially separated from the rate of exchange of the French Franc on January 25th, 1944 after the signing of the Franco-Anglo-Lebanese-Syrian Accord whereby the Lebanese Government would now be free to set its own rates of exchange.

On January 24th, 1948 this monetary emancipation was formalized in a Franco-Lebanese Agreement by which the Lebanese Government redeemed control of all its monetary instruments, including the freedom to hedge the value of its currency in circulation, and in which it also obtained certain guarantees assuring its freedom to choose the base and/or the comparison elements of its currency.

Lastly, on May 24th, 1949, a monetary bill was passed which not only set the consistency of the financial cover but also committed the government to full responsibility of its monetary policy whereby all monetary regulations, incorporated in the charter of the Issuing Body since 1937, were dissociated from the conventions between the Government and the Central Bank..

Thus through such engagements, the Lebanese Government obtained the essential prerogatives to establish its own independent monetary and financial policy. Although never clearly defined as such, in view of the financial regulation instituted in 1944, it can be argued that these prerogatives produced the blueprint for the “liberal policies destined to establish Beirut as a center of international arbitrage and monetary exchange operations”.

Two basic monetary arrangements made this possible. First, by the gradual distancing of the foreign exchange market from wartime restrictions, and second, by strengthening the national currency in such a way as to make sure that it remained a relatively stable instrument if not an actual monetary haven.

In spite of legislative and regulatory ambivalence, reticence and doubt, the program produced results. The current general consensus amongst international experts is that the Lebanese monetary experience, against all the odds, is a success and not only sustained the country throughout its period of peacetime economic adjustment but was the perfect instrument for the future success of its commercial enterprise.

Nevertheless, although the experience is deemed to have been a big success, looking in from the outside and from the view of those pundits unaware that it is impossible to predict the balance of accounts and the balance of payments of a country based solely on that country’s statistics and trade figures and who thus predicted that the currency was potentially unstable, it is true that a number of factors, problems, and theories ill-suited to a particularly Lebanese environment did produce distorted figures which means, in impartial terms, that the experience cannot be described as a complete and resounding success.

Indeed, in order to install a mechanism for the free exchange of currencies, a prerequisite essential to the very continuance of the country, the period of transition had to be carefully managed in order to gradually introduce a device as delicate as a Free Market, which is why it was carried out in two stages. The first stage involved maintaining a foreign currency around which the rate of exchange would pivot. The second involved the introduction of a completely free currency exchange market underpinned however by a “Currency Exchange Stabilizing Fund” designed to be used in the event of abuse.

The first stage was very effective and maintaining the pivotal currency was not too expensive for the State as it was based on the occasional sale of French Francs at an artificial rate and by allowing fixed trading in other currencies. The second stage was another matter. A completely free market was hampered by the inability of those natural market regulators, the large Banks, to intercede at will handicapped as they were by the withdrawal of currencies at a predetermined artificial rate, especially during changing market trends. The Currency Exchange Stabilizing Fund proved inadequate due to a lack of necessary funds.

It was argued that a wholly free market would imply and presume an alteration of past agreements between certain foreign companies and the Office of Foreign Exchange and would allow the State to fund, on favorable terms, its currency spending as well as reinforce its monetary cover. In fact, this did not occur with the advent of total fiscal freedom due in part to the actions of the regulators and due in part to market operations which had a tendency to stabilize things.

With regard to the Currency Exchange Stabilizing Fund, it has to be said that its objectives and how it was designed to work were never properly understood and that it was paralyzed from its inception even though it was essential to steady the first few steps of a pioneering new Free Market.

Lastly, certain highly respected theorists failed to ‘read’ the overall nature of the Lebanese market and what it offered in terms of its potential, and, one must add, its responsiveness. Bewildered by the notion of a ‘Free Market’ they came up with disquieting theories on the convertibility of a currency, such as the risk of taking a major currency supported only by its future potential and its balanced accounts onto an international scale and the desirability of reintegrate it (some say still want to reintegrate it) with a lower scale of currencies by linking it to a dominant foreign player…

Letter

Lebanese Legation to France

Lebanese Ministry of Foreign and Expatriate Affairs

HE H. Frangié

Paris October 4th, 1947

To the President of the Republic Beirut

Mister President

Today we held the third meeting of the Franco-Lebanese-Syrian Conference. The first meeting, consisting purely of formalities, was opened by Mr. Teitgen, the French Deputy Prime Minister and acting Minister for Foreign Affairs, who welcomed us and hoped that the meeting would end in success in order to rekindle our old cordial relationship.

I replied in kind assuring him of our sentiments of goodwill and our shared hope of amicable relations with France. Khaled Bey replied more or less also in kind.

After the exchange of speeches, Mr. Teitgen withdrew leaving in his stead Mr. Gazel, the French Plenipotentiary Minister to New Zealand. Mr. Gazel, who happens to be in Paris and a former Chairman of the Department of Trade Agreements at the Quay d’Orsay, will lead the French delegation as the regular French candidates are currently handling negotiations in Geneva, London and New York. He asked us to submit the issues we wished to negotiate and each delegation tabled their own points for discussion.

On our behalf, I requested that we discuss the currency issue, the wartime management of the Railway, the Tripoli refinery, the Lebanese Labor Force, the emigrants in Dakar, the Citrus Fruit Sector, and the matter of shareholdings in companies operating in Lebanon but headquartered in France.

Khaled Bey seconded the topics which carried mutual ramifications, overlooked the topics deemed of purely Lebanese interest and to my great surprise announced that he would be seeking to negotiate a trade agreement.

At the second meeting, a three-part list had been drawn up. The first included topics to be discussed by all three parties and the second those topics to be discussed with Syria alone.

The French requested concessional arrangements on behalf of French companies, payment of certain outstanding debts such as the Syrian Telephone Service, the cost of Radio-Levant, the costs incurred by the Special Troops, and the settling of French possessions.

Mr. Gazel further requested that each delegation discuss the topics of interest to them but leave the currency issue aside. We replied that the currency issue ought to be given priority but the French held that the currency issue could only be examined after all outstanding debts had been satisfactorily discharged.

Although I pointed out that the issue was primarily a legal matter, they were manifestly determined that it be subject to the resolving of the outstanding financial debts as laid out by them in the original agenda. Moreover, Mr. Gazel stated before the end of the second session that the solution to the monetary question […]

The first thing we addressed was the wartime management of the Railroad. After wasting a lot of time and a short statement from Gébara, we finally realised that it boiled down to a matter of accounts but that the exact amount involved was unavailable as they had yet to receive monies owed to them by the British.

The second topic we moved on to was the refinery in Tripoli. The French were willing to admit that they had committed themselves more or less to 9 million. Mr. Gébara went beyond the agreement with Emir Jamil Chéhab and asked that custom duties be paid on the share of refinery products delivered for local consumption. The French then further arranged with Emir Chéhab to the sharing out of the profits in which a 57% share would be assigned to Lebanon and Syria. I concluded that in order to negotiate on behalf of the two countries, Syria must have given some kind of mandate for this. I requested a postponement and have asked Beirut for clarification.

The French throughout pursued their arguments about the cost of the Special Troops. I vigorously refused to engage with them on this matter and replied that Lebanon and of course Syria did not recognise any such debt.

This afternoon we talked about the monetary issue.

We based our case on the correspondence exchanged with the French legation in Beirut. The French maintained we were out of order and I argued that the question was academic but that there was plenty of time to address the legal aspect later if we did not manage to see eye to eye but in the meantime, the priority was to discuss and settle the new monetary cover arrangements.

We are to reconvene on Monday at 4:00 to continue this topic. I think we will be nominating a sub-committee where I intend to pursue the discussion. In the meantime, I will be discussing the Lebanese Labor Force with other representatives whilst the Syrians will be addressing purely Syrian issues with the French.

After these preliminary encounters and according to reliable sources, I believe that the French will be more conciliatory on the monetary issue than they might have been on matters that are of particular interest to France which is why, for our sake, I insist that the Syrian Government instructs its delegation to take a broader stance on things.

My fear is that the Syrians will side with the French on matters concerning the interests of French companies. I think we ought to remind the Syrians that they are here to jointly negotiate and that under no circumstances will they be allowed to avoid negotiations involving their partner’s interests. We must present a united front determined to settle all contentious issues together for a conclusive end to all the friction between France and ourselves, if only on the monetary, financial, and economic fronts. In return for their compliance, I believe we will find the Quay d’Orsay very keen to reach an agreement with us especially as it does not have the final say in what is essentially a Treasury matter.

The latter are inclined to use the Anglo-Egyptian example as a precedent. There, England asked the Egyptians outright how much they were prepared to contribute toward the cost of the war and as such, to what extent could they expect England’s debt to be reduced. I will avoid that road and I believe that the Quay d’Orsay will offer us an interesting proposal if it is perceived to be in the general interest of France assuming they can persuade the Treasury to follow their lead and especially if it produces some concrete results. The latter is the sensitive spot in the discussions and it is on this point that I would like you to personally intervene with the Syrians in order for those of us here to act more freely.

I have to admit that the first approach was not encouraging. Khaled Bey started by saying that he was waiting for instructions from his Government and that he was not at liberty to discuss either the monetary issue or the commercial agreements. Already on our guard with them, his attitude has added a degree of chilliness to the relationship. Gébara, whom you know so well, didn’t help either with his intercessions. Nevertheless, at this evening’s meeting, Khaled Bey made reassuring noises with regard to the Railway which is good news for us and I left this session feeling more optimistic than I did yesterday.

Like Van Zeeland, I cannot stress enough that our priority above all is to protect the currency and whatever it might cost us in concessions on other issues, it should not stop us from that. Of course, it goes without saying that I will do my best to see that all our concerns are tackled with equal zeal. This report is, of course, only a preliminary picture at the start of negotiations which are bound to prove difficult. It is based on personal impressions and a little information rather than on actual facts.

Allow me now, Mr. President, to thank you for the very kind words passed on to me by Emile Khoury. Having only arrived in Paris the day before yesterday he is already assisting me in a quite number of tasks. I have no doubt that he will be of great help.

Yours respectively,

H. Frangié

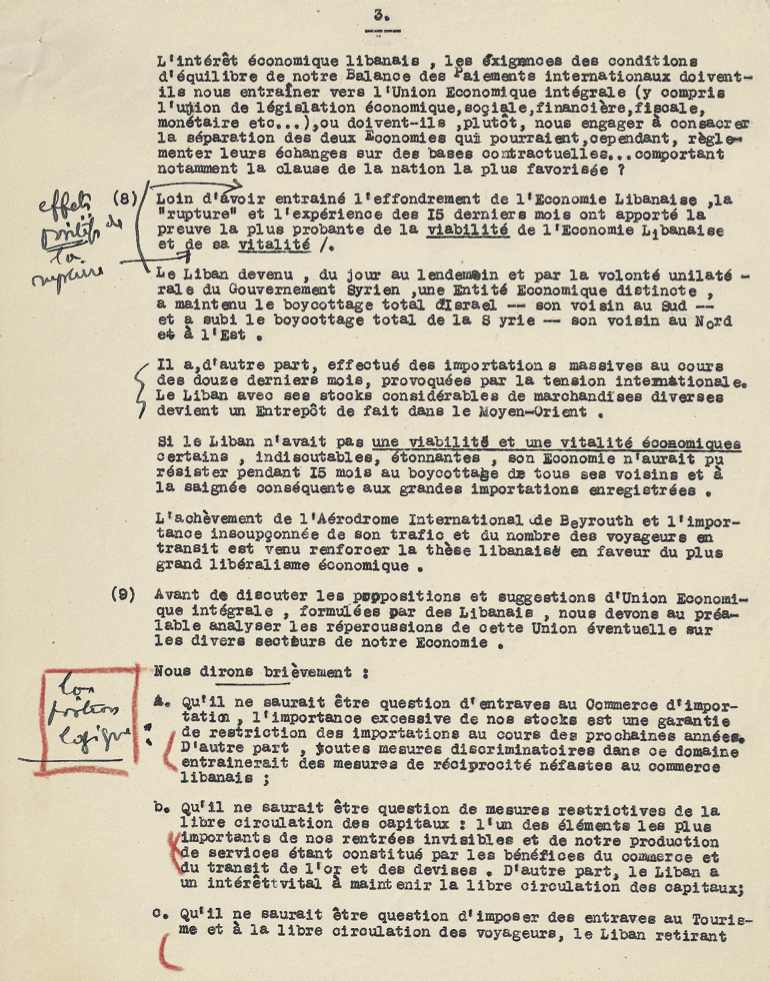

Renewal of the Syrian-Lebanese Trade Union in 1953.

In 1953 Lebanese-Syrian trade relations were, once again, on the agenda. One year before Michel Chiha passed away, President Camille Chamoun announced on October 28th, 1953 his desire to see the economic union between Syria and Lebanon re-established. A treaty was signed to that effect on March 5th, 1953, renewed on August 13th the same year, and later extended for six months on March 25th, 1954.

In the gallery below you will find a copy of Michel Chiha’s thoughts on the renewal of the Syrian-Lebanese Trade Union.